Now widely regarded as 'The Father of Aeronautics', Sir George Cayley (1773-1857) evolved the idea of an aircraft with fixed wings, in which the principle of lift was separated from the propulsion system, and in which inherent stability, as well as tail-unit control-surfaces, must be incorporated.

Born in Yorkshire in 1773, Sir George Cayley was an English country squire whose estate was in the village of Brompton near York.

Very well educated in science and mechanics, he applied a rigorous approach to the problems of flight because, with clear and great vision, he knew that the ability to navigate "the ocean that comes to the threshold of every man's door" was a most important goal.

By 1799, he had realised the fundamental importance of lift to balance weight and thrust to overcome drag - as indicated by the engraving on the famous Cayley 'coin' that is kept in the London Science Museum. Most importantly, he recognised that, for heavier-than-air flight, "the whole problem is confined within these limits, viz, to make a surface support a given weight by the application of power to the air."

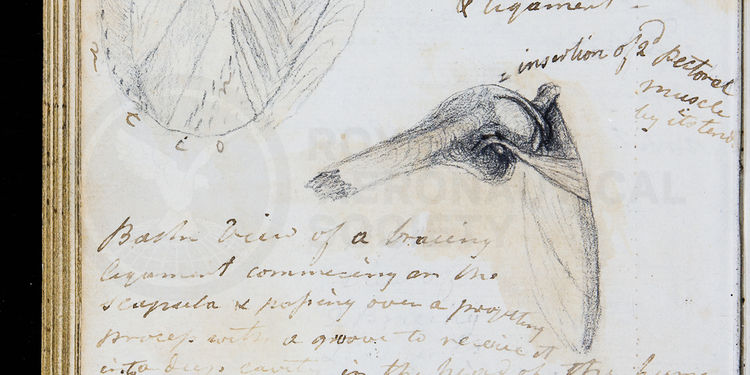

By examining the gliding characteristics of birds and observing the relationship between wing size and body weight, he determined estimates for realistic wing loading e.g. for a crow, 1lb/ft2 at 35ft/sec and 6° incidence. He also realised the importance of minimising drag and he recognised the effect of the afterbody, proposing that the geometry of a trout was a good 'streamlined' shape.

This knowledge gave him the ability to design machines with physically realisable characteristics.

His research led Cayley to the conclusion that the single most difficult problem facing the would-be aircraft constructor was the availability of a suitable power unit. Being well aware that the steam engines of his day produced too little power for their weight, much of his work was (fruitlessly) directed towards the development of an efficient air engine.

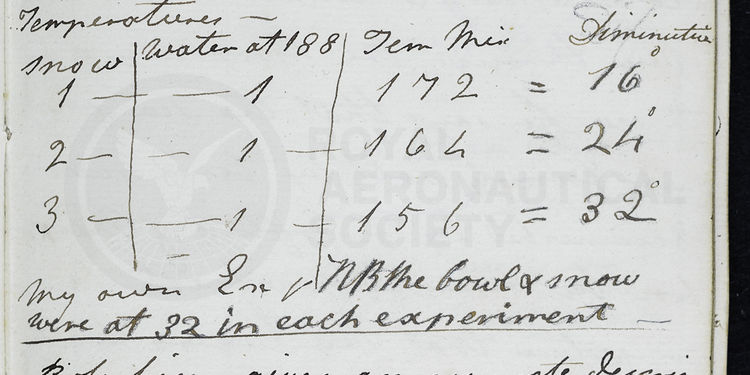

Nevertheless, out of his own pocket he was able to conduct a series of celebrated, scientifically sound glider experiments some of which, it is rumoured, carried human payloads. The results obtained were used to further develop his ideas and this demonstrated how he used the combination of scientific method and engineering skill to great advantage.

With the realisation that manned, heavier-than-air flight was a long way off, he studied the issues surrounding lighter-than-air transport. This was a pragmatic approach and, by applying his experience and analytical skills, he deduced that to be of any real value balloons had to very large and, if they were to be propelled, they should be streamlined rather than spherical. With amazing foresight he was outlining plans for powered airships that could lift 50 tons, long before Count von Zeppelin was born.

Despite the fact that his sound approach to the general problems of aerial navigation told him that one man, of relatively modest means, could not produce useful machines with the technologies available at the time, he maintained the vision and made special efforts to interest others.

In order to enlarge the number of minds focused on the problems, he made three attempts to form an aeronautical society. The first was in 1816, the second in 1837 and the third in 1840. All ended in failure. However, Cayley did have some support, notably from his friend the Duke of Argyll, and it was just nine years after Cayley's death that success was finally achieved when the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain was formed with the Duke of Argyll as its first President.

Although he never lived to see any of the work that he started come to fruition, it is a measure of the man that his vision was so clear that he never wavered in his efforts to pave the way for future solutions.

He was truly remarkable.

Charles Harvard Gibbs-Smith Hon CRAeS delivered a lecture on the subject of Sir George Cayley to the Royal Aeronautical Society’s Historical Group in 1973. You can listen to a recording of this fascinating lecture from the Aerosociety Podcast.

Related Collections

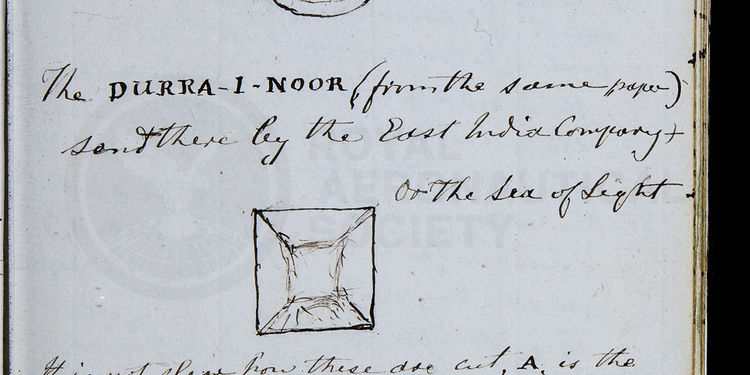

Sir George Cayley's Notebook - 'Egypt' Part A (1848-1855)

In his lifetime, Sir George Cayley (1773-1857) published just a few papers on the subject of aeronautics and many of his ideas are explored in five illustrated…

Sir George Cayley's Notebook - 'Egypt' Part B (1848-1855)

In his lifetime, Sir George Cayley (1773-1857) published just a few papers on the subject of aeronautics and many of his ideas are explored in five illustrated…

Sir George Cayley's Notebook - 'Motive Power' (1793)

In his lifetime, Sir George Cayley (1773-1857) published just a few papers on the subject of aeronautics and many of his ideas are explored in five illustrated…

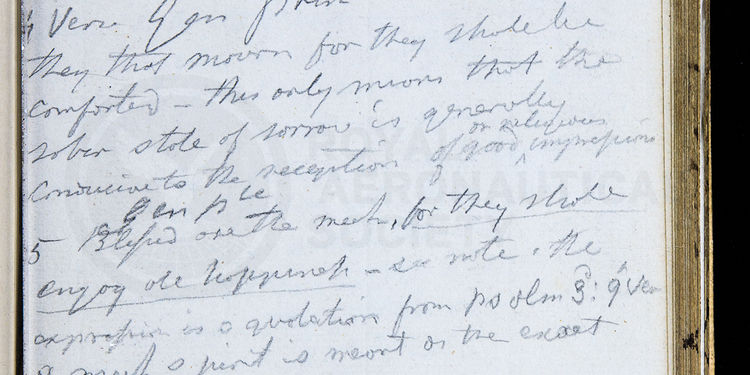

Sir George Cayley's Notebook - 'Passions' (1812-1830)

In his lifetime, Sir George Cayley (1773-1857) published just a few papers on the subject of aeronautics and many of his ideas are explored in five illustrated…

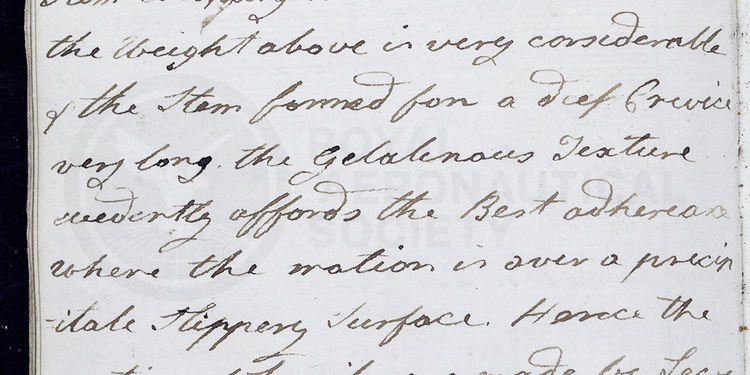

Sir George Cayley's Notebook - 'Sea' (1799-1811)

In his lifetime, Sir George Cayley (1773-1857) published just a few papers on the subject of aeronautics and many of his ideas are explored in five illustrated…

Sir George Cayley's Notebook - 'Vol 1' (1795)

In his lifetime, Sir George Cayley (1773-1857) published just a few papers on the subject of aeronautics and many of his ideas are explored in five illustrated…

Sir George Cayley's Schoolbook (1780)

This is one of Sir George Cayley's schoolbooks which includes his earliest sketches of a flying machine alongside other remarkable drawings.